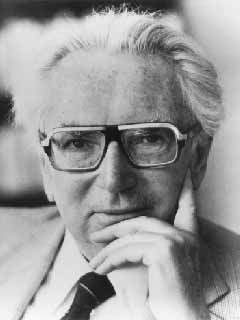

When I was in college I read Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search For Meaning and was really gripped by it. Frankl (1905-1997) was a Jewish psychiatrist, neurologist, and holocaust survivor. In the book he reflects upon the question of meaning in life and explores what made the difference between those who survived the concentration camps and those who did not. Frankl references Nietzsche’s dictum, “he who has a why to live for can bear with almost any how,” and argues that what made the difference between those who survived and those who did not was not the intensity of their suffering, but whether or not they retained meaning and purpose in their lives.

When I was in college I read Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search For Meaning and was really gripped by it. Frankl (1905-1997) was a Jewish psychiatrist, neurologist, and holocaust survivor. In the book he reflects upon the question of meaning in life and explores what made the difference between those who survived the concentration camps and those who did not. Frankl references Nietzsche’s dictum, “he who has a why to live for can bear with almost any how,” and argues that what made the difference between those who survived and those who did not was not the intensity of their suffering, but whether or not they retained meaning and purpose in their lives.

Here are some quotes:

“We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

“Fundamentally, therefore, any man can, even under such circumstances, decide what shall become of him – mentally and spiritually. He may retain his human dignity even in a concentration camp.”

“When we are no longer able to change a situation — just think of an incurable disease such as inoperable cancer — we are challenged to change ourselves.”

I don’t know enough about Frankl to know whether or not I would agree with him on how we define and discover meaning. But I think his point that the ultimate question of life is not determined by our circumstances is profound and decisive. What gripped me most about this book, and has stayed with me to this day, is not the horror and barbarity of his experiences in concentration camps – when you pick up a book about the holocaust, you expect that. What really struck me was Frankl’s repeated insistence that even there, in the most inhumane and horrific conditions imaginable, the greatest struggle is not mere survival. The greatest struggle is finding meaning. As I was reading, I was struck with this thought: going to a concentration camp is not the worst thing that can happen to a person. The worst that can happen to a person is not having a transcendent reason to live. Life is about more than finding comfort and avoiding suffering: its about finding what is ultimate, whatever the cost.

As a Christian, I am so grateful that God has worked in my life, despite me, to bring me into a relationship with Him. This relationship has brought more meaning, purpose, and joy into my life than I ever would have thought possible. I never would have guessed it or discovered it on my own: knowing Jesus Christ is the great treasure worth pursuing in this life. He is the secret answer to all of life’s uncertainties and longings. “Now this is eternal life: that they may know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom you have sent” (John 17:3).

After finishing Frankl’s book one night in December 2005, I went home and wrote this in my journal:

The difference between the life of a victim of Auschwitz and a contemporary wealthy American is a mockery. One believes that happiness can be attained by possessing the latter life and avoiding the former. A lie! Both lives face the same suffering, the same struggle. This is by no means a depreciation of the magnitude of the horror and the evil of the holocaust. Rather it is the recognition that no amount of political liberty, material wealth, or freedom from physical pain can bring meaning and ultimate happiness into life. Political freedom and material possession are good and valuable things for which we ought to be grateful, but they do not bring us the answers to life’s deepest questions. No man comes to know his heart and his soul through the attainment of wealth or the absence of suffering. No amount of women, fame, or luxurious living can give a man a reason to fight for his life if he should lose it all. With regard to life’s ultimate question – the discovery of meaning in an apparently meaningless world – the prisoner in Auschwitz has advantage over the free and wealthy man in that life is presented to him more honestly, with less seducing distractions. And yet no man, however free and wealthy, is denied the pursuit of meaning, if he should sell his life in its pursuit.

The difference between being crucified and lying in comfort is nihil compared to the difference between purpose and purposelessness. What all men seek is equally distant to the most unequal of men, and equally worthy of the most unequal of sacrifices.

5 Responses

Gavin, I was just reading about Frankl in Stott’s “Why I Am A Christian”. Very moving and thought provoking. So much of our life experience, whether rich or poor, in ease or struggle is lived between our ears and in our hearts. It makes me think of Paul converting his jailers while he was being persecuted. Thanks for this. Love to you and your sweet bride.Laurie

Thanks Gav.

Thank you, Gavin, for these deep thoughts.

Amen, brother.

Enjoyed your blog. Keep up the great insights.